From Forests to Future: The Power of Native Reforestation in Supporting Kenya’s Local Climate

By Anita Field, With contributions from the IGAD Climate Change Technical Working Group

According to recent data on land cover and land use change, it is evident that Kenya has experienced a considerable decline in tree cover, with a loss of 360,824 hectares, between 2001 to 2020 (Butler, 2022). As reported by the Kenya Forest Service (KFS), the current extent of tree cover accounts for a mere 12.13% of the country’s total land area.

Embracing the harsh reality of forest loss and recognizing its significance has prompted a remarkable wave of commitment toward reforestation. This display of environmental stewardship illustrates a collective determination to restore our depleted landscapes. Yet, as we embark on massive tree-planting campaigns and make bold pledges to revive Kenya’s degraded areas, could our efforts unknowingly sow the seeds of unintended consequences?

© Kenya’s First Lady Rachel Ruto during a tree planting exercise at Kakamega Forest on June 8, 2023. The First Lady has pledged to spearhead the restoration of a substantial 500 acres of degraded land within the Kakamega Forest.

It is important to consider the potential risks and impacts associated with non-native reforestation efforts. Planting non-native tree species may do more harm than good to the precious local climate. The following are how these well-intentioned endeavors could lead astray:

- Different tree species vary in their ability to store carbon. Some non-native trees are not as good as native trees at capturing and storing carbon from the atmosphere.

- Native trees are better adapted to handle local climate challenges. Planting non-native trees can lead to increased tree deaths and less resilience in the face of changing conditions.

- Non-native trees may have different water needs, potentially increasing irrigation demands and worsening water stress during droughts.

- Non-native tree species can disrupt the timing of biological events, affecting the interactions within ecosystems.

- Certain non-native tree species are more prone to wildfires, posing risks to people and natural areas in fire-prone regions.

- Non-native tree species can alter local microclimates, causing divergent effects on temperature, humidity, and other climate factors in different ways than native species.

The Eucalyptus tree, a prominent non-native species present in various ecological zones of Kenya, serves as an example of how it disrupts the local climate.

© Veronica Todaro Collection — iStock/Getty Images

Often planted for its commercial value, this tree’s unquenchable thirst drains water resources, leaving the land parched and barren. As a result, the once vibrant soil loses its biodiversity, its very essence eroded. The tree’s bark and oils, prone to fueling fires, cast ominous shadows of destruction upon delicate ecosystems.

Meanwhile, microclimates quiver, as such species prove inadequate in their long-term carbon sequestration abilities. (Castro-Díez et al., 2021)

In our quest for progress, we must recognize that the economy and environment go hand in hand, especially as we become more climate-conscious.

While certain species may be prioritized for their short-term benefits, it is the bigger picture that promises true rewards. Reforestation initiatives in Kenya, focusing on the cultivation of native tree species, present an opportunity to enhance the local climate while supporting the local economy.

Instead of relying on costly imported species that contribute little to the local environment but line the pockets of a few, the promotion of indigenous tree species can yield multiple advantages. Species such as Acacia boast deep root systems that help with water retention and soil stabilization, making them valuable for combating desertification and erosion in ASAL regions.

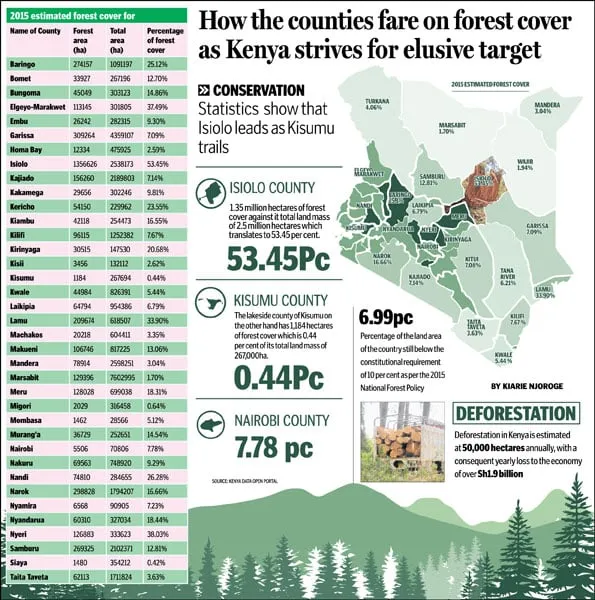

© Business Daily Graphic

The Mukinduri, African Olive, and African Cherry are sustainable alternatives to the Eucalyptus. The native species not only present economic potential but also enrich the soil and provide natural habitats for wildlife. These are just a few glimpses into the vast array of native tree species in Kenya that have the potential to improve the local climate by supporting biodiversity, enhancing carbon sequestration, and promoting ecosystem health.

© A Kenyan pupil plants a tree in Kakamega Forest on June 8, 2023.

Moving forward, it is essential to spread knowledge about biodiversity conservation, fire risk prevention, erosion control, and the water cycle, enabling local communities to recognize the value of native species in preserving a thriving ecosystem and a balanced climate. Through more informed reforestation efforts, Kenya can harness the power of native trees to create a more sustainable and climate-resilient future.

References

Castro-Díez, P., Alonso, Á., Saldaña-López, A., & Granda, E. (2021, March 1). Effects of widespread non-native trees on regulating ecosystem services. Science of The Total Environment. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969721012080

Butler, R. A. (2022, February 21). 2022 deforestation statistics for Kenya. Mongabay. https://rainforests.mongabay.com/deforestation/archive/Kenya.htm